“Measure what can be measured, and make measurable what cannot be measured.”

– Galileo Galilei

After (suffering) experiencing IGCSE for 1.5 years, I have to say, I’m not amused with the workload I’ve had to deal with, although I know it’ll only get worse from here. Still, I have to say I’m insanely grateful for all that I’ve had the opportunity to learn and understand, and I’m even more grateful that I’ll have the chance to continue my education with IB program (and hopefully do well enough with that).

Before I can lounge and relax, however, now that the semester assignment is coming to an end, I have to, of course, write up a math e-journal to get 30% of my final grade. For this particular assignment, we’ll be discussing IB questions that should hep us gain a better understanding about math.

Part a: Investigation A: A Very Safe Plane

You’re sitting in the cockpit, leaning relaxedly but just straight enough that if needed, you could quickly commandeer your plane manually. Behind the relatively narrow, aluminium door behind you sits rows upon rows of people awaiting that small thump that will tell them they’ve arrived. After a long 8 hours, it’s finally time to land. Will you make it through the runway?

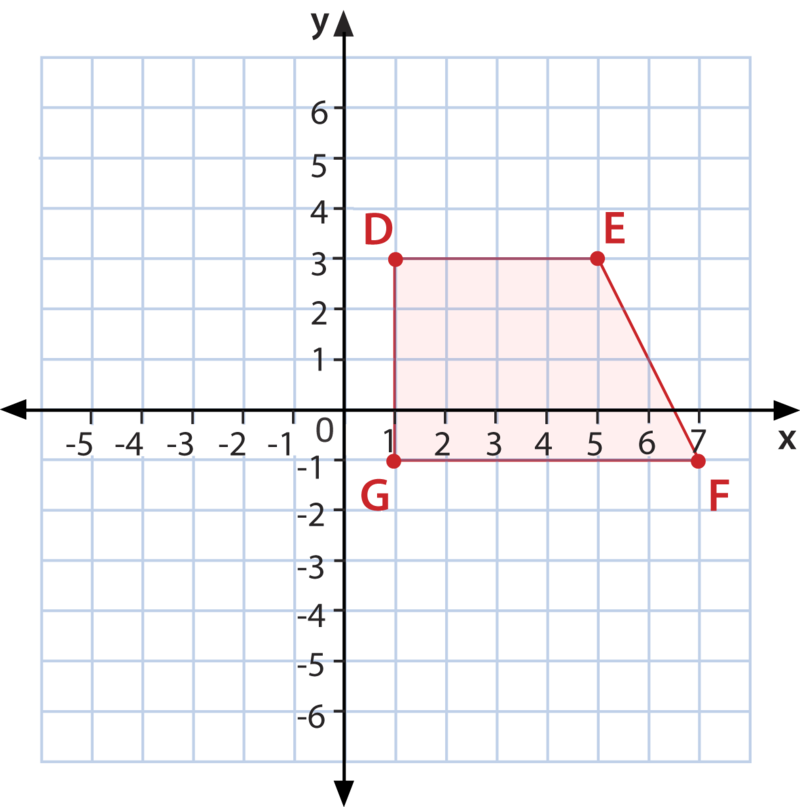

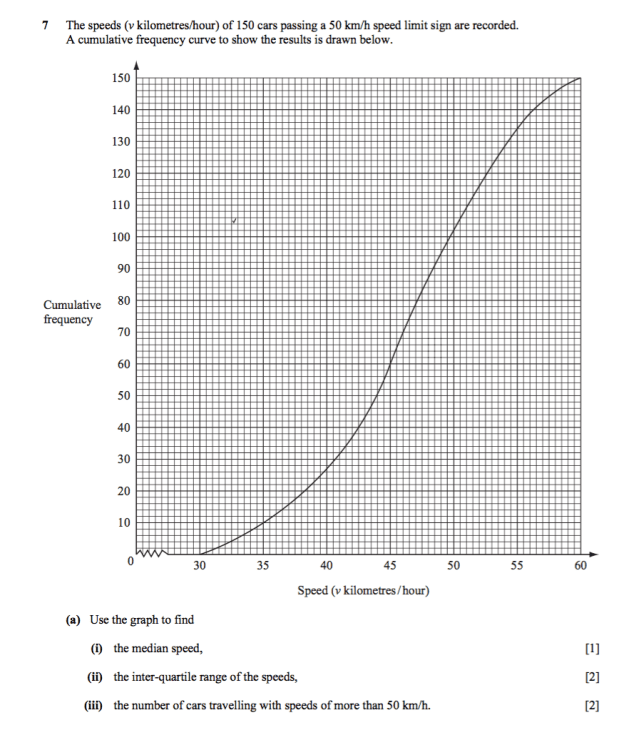

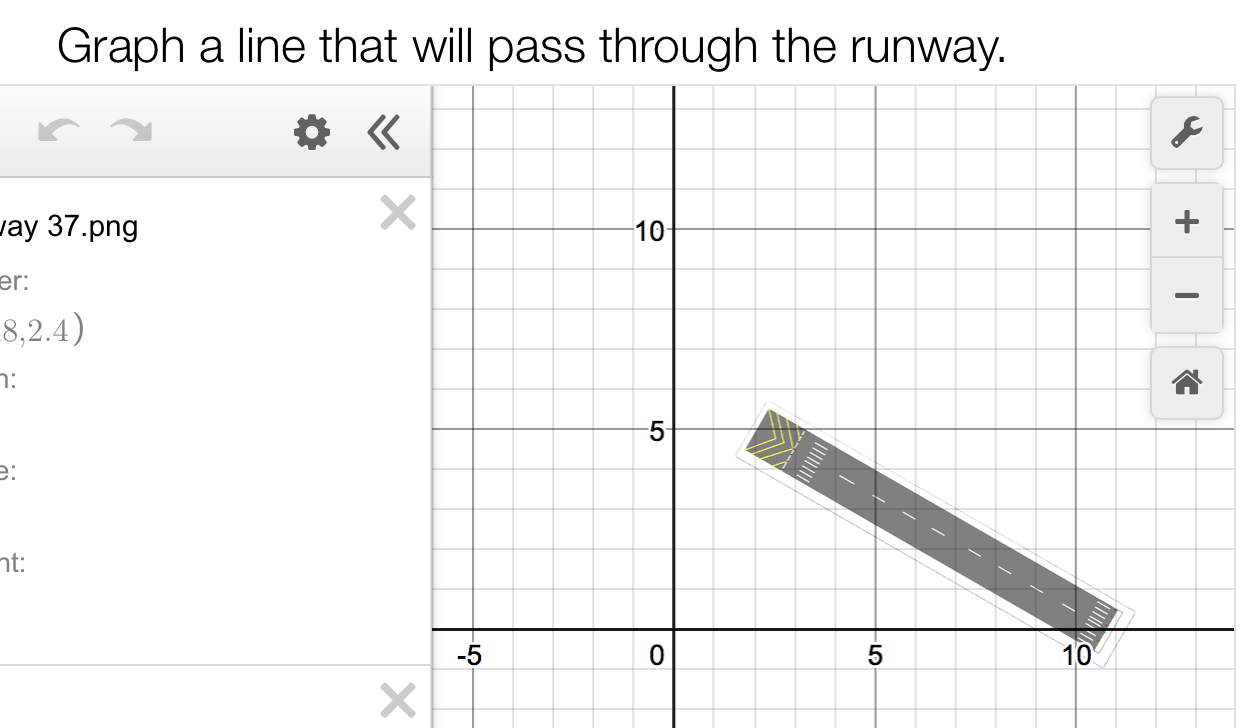

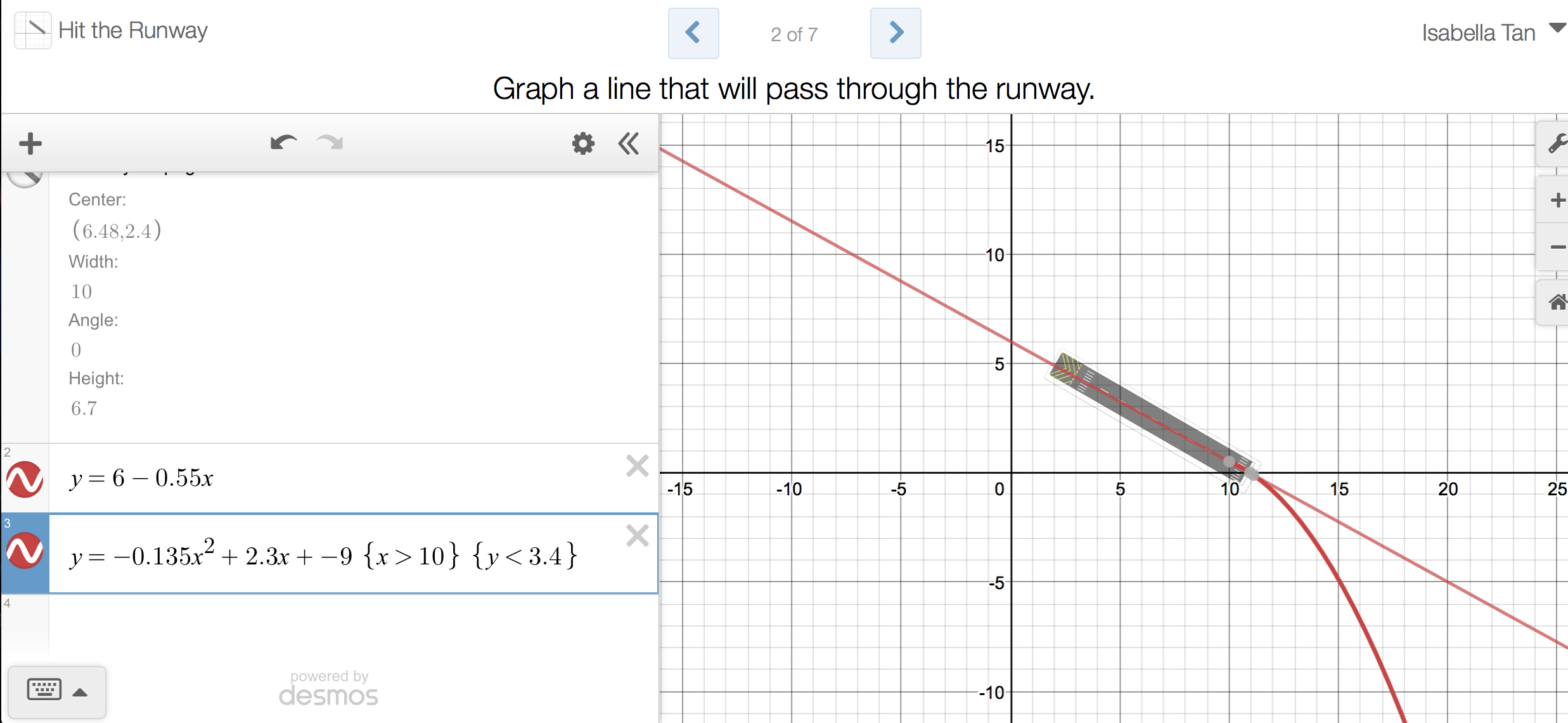

We were given 7 runways and for each of them, we were supposed to construct a line which would represent a plane’s path as it descended onto an airport’s runway. The main goal was, of course, to ensure our flight’s mortality rate was 0%.

The topics involved in this task are, of course, geometry, particularly linear equations, or equations where the highest power is 1.

Of course, we all know that the formula for a straight line is y=mx+c where m is the gradient and c is the y-intercept, or where the line cuts y-axis. To solve these questions, this one in particular:

I first entered the variable y and the ‘=’ sign, before inputting the y-intercept; where I predicted the line would cut the y-axis by imagining a line passing through the white stripes symbolizing the middle of the runway that would extend to the y-axis. In my mind, this line cut the y-axis at 6, so the equation became y=6. Of course, this would produce a completely horizontal line if I left it as is, so I turned to find the gradient of the line.

Now that I had one of the coordinates of the line – (0, 6) from the y-intercept – I turned to find the point where the line cut the x-axis. Once again, I extended my line and found that it would cut the x-axis at the point (11, 0).

With these two points, I could find the m or gradient of the line using the formula (y2-y1)/(x2-x1). This got me to (0-6)/(11-0), which is -6/11, which rounds off to -0.55.

Therefore, the line equation I entered for that question was y=6-0.55x.

While I used a line and line equation to solve this problem, as advised by some JC students, it’s also possible for the plane to curve or circle the runway before touching it instead because, in real life, sometimes the plane isn’t parallel with the runway and needs to turn to reach it. For this investigation, I added a curve showing what a plane might turn like to get to the run away. This was done by playing around with dismiss and changing the numbers for variables a, b and c of the quadratic equation and adding limits for the curve so that the plane didn’t overshoot the runway.

Part B: Investigation B: Koch‘s Irritable Snowflakes

(2019). Education Bookshelf Mathematics Analysis and Approaches Higher Level.

[online] Bookshelf.oxfordsecondary.co.uk. Available at:

https://bookshelf.oxfordsecondary.co.uk/contents/428/index.html [Accessed

30 Oct. 2019].

| Iteration no. | Perimeter (cm) | Area (cm^2) |

| 1 | 243 | 2841 |

| 2 | 324 | 3788 |

| 3 | 432 | 4209 |

| 4 | 576 | 4396 |

Overall, the model for the area and perimeter would be:

Perimeter = 81/3^(iteration no-1) x 3(4^(iteration no-1))

Area = (previous iteration’s area)/3^(iteration no) x 3(4^(iteration no-1))

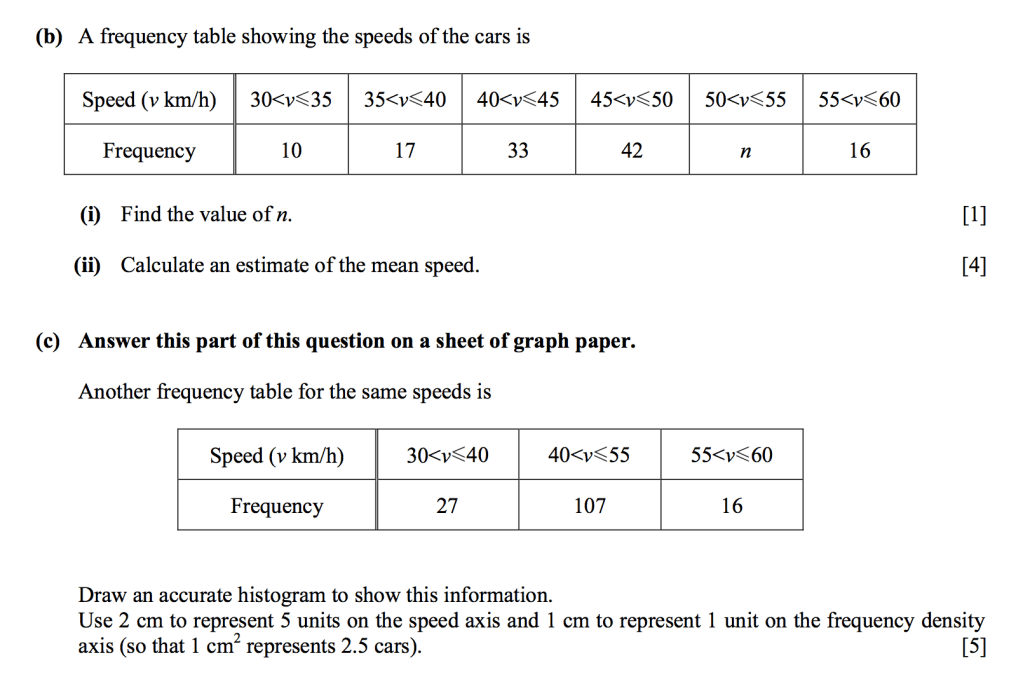

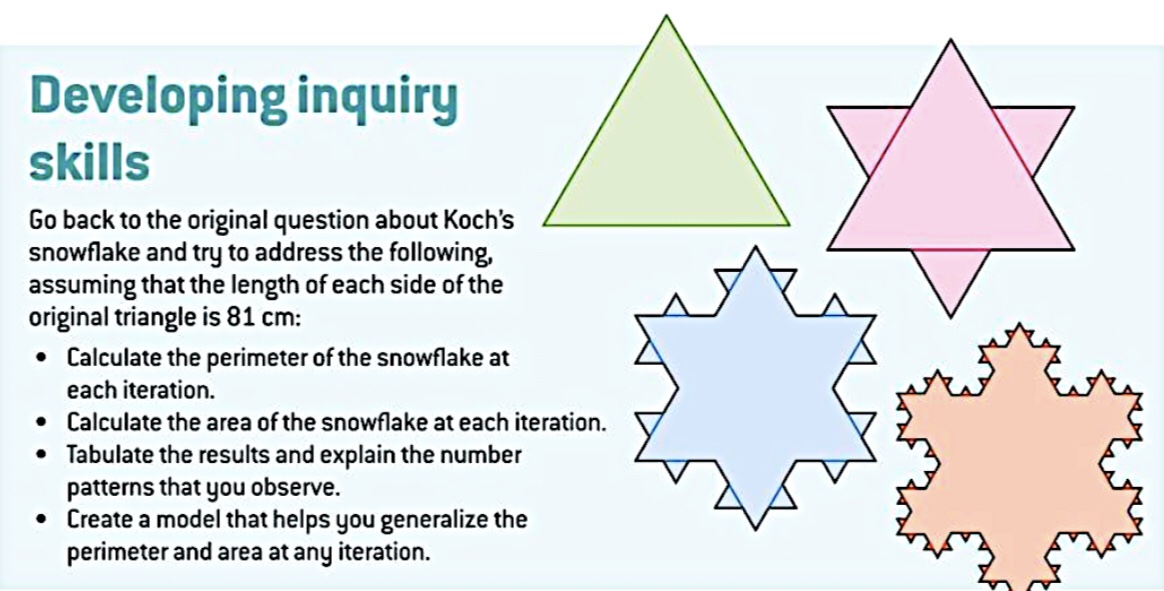

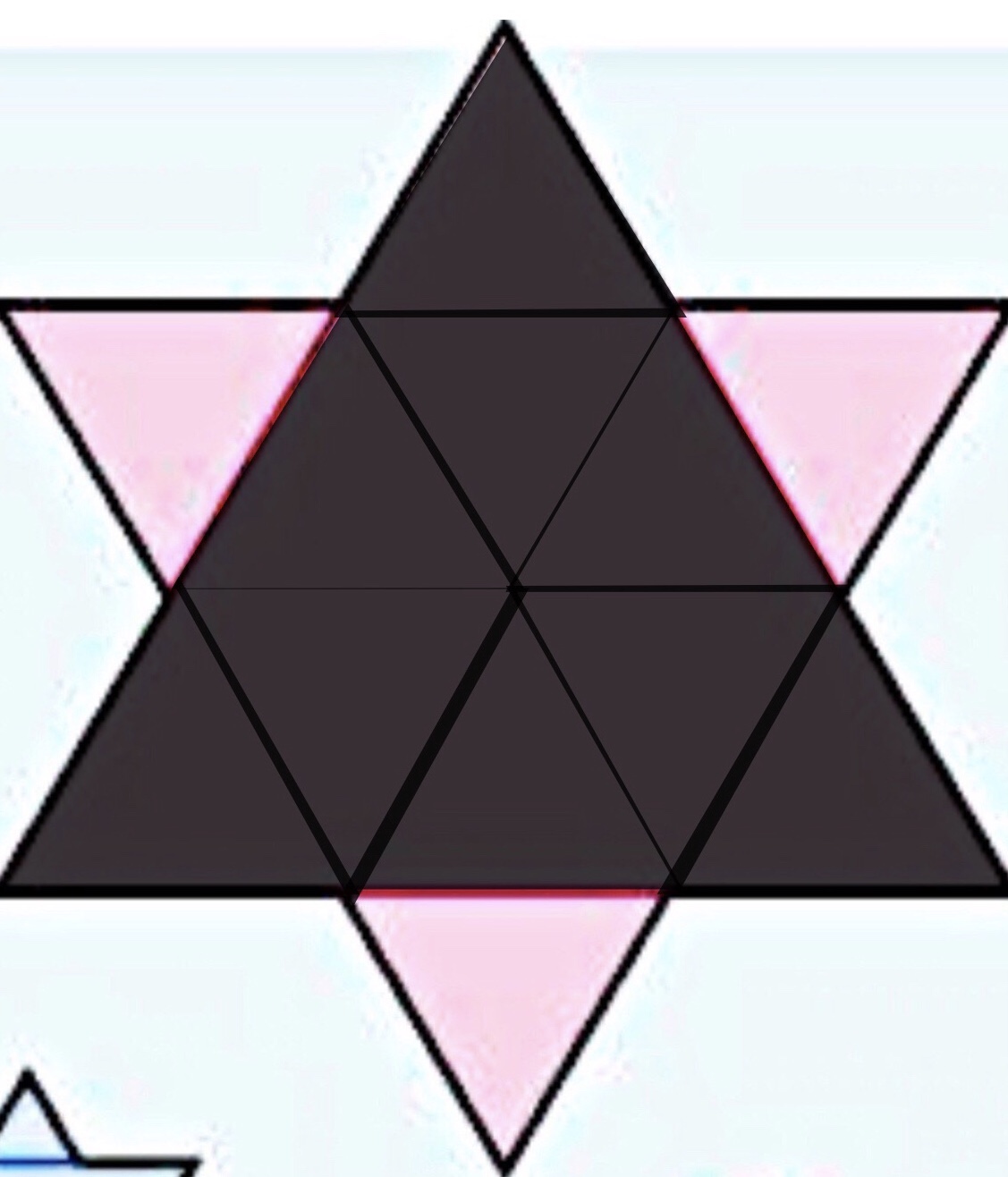

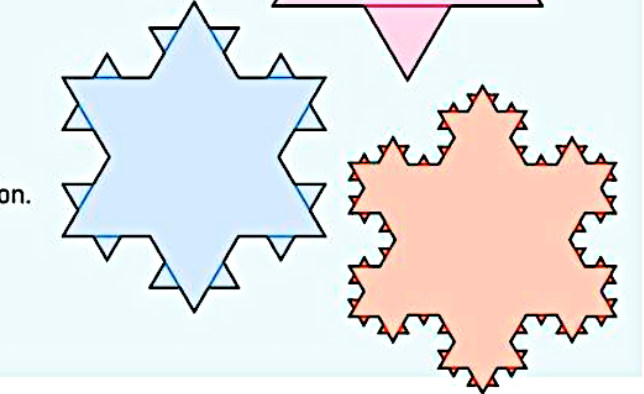

So, this time for this task, we need to explore koch’s triangle and find the perimeter and area for its different iterations, tabulate the results and find a formula we can use to find the perimeter and area of any iteration of Koch’s triangle. The topics involved here are the area and perimeter formulas of a triangle, geometry, geometric sequences and infinity.

Anyway, the key to solving the perimeter and area of his snowflakes is to know the length of the triangles, as all his triangles are equilateral and every other variable we need to know can be calculated using this length.

We initially know the length of the largest triangle is 81 cm.

Next, we can divide this large triangle into smaller triangles by dividing it into the protruding smaller triangles added in the first iteration of the snowflake.

As we can imagine, one side of the original triangle, makes up three smaller triangles’ lengths. And as all the triangles are congruent and equilateral, we can deduce that the length of the smaller triangle is 81/3, which is 27 cm.

This goes on for the next two iterations of the triangles; we just keep dividing the previous iterations’ length by 3. As a result, we can make a formula for the length of each side of the triangles’ iteration:

Length (iteration no) = 81 /3^(iteration no-1)

Therefore, to find the perimeter of each triangle, we just need to multiply the length of the triangle we found using the above formula and multiply it by the number of sides a triangle has.

As for the area of the iterations, for the first triangle, obviously, we can use the standard triangle formula, which is 1/2 x base x height, which in this case becomes 1/2 x 81 x height. Since it’s an equilateral triangle, the way we can find the height is to cut the triangle in half to make two right angle triangles and use Pythagoras’ theorem. This would make the height 70.15 round off to two decimal places. Therefore, the area of the first triangle would be 2841 when round off to whole number.

The next few iterations are more troublesome. For the next triangle, we can just divide the previous iteration’s area by 9 to get the area of the smaller triangles, which is 315.68, and then multiply it by the number of smaller triangles in this iteration, which is 12 as the original triangle had 9 smaller triangles and 3 additional smaller triangles were added with one on each side of the original triangle. So the second iteration’s area would be rounded off to 3788.

For the next iteration, we divide the area of the smaller triangle by 9 again to get the are of the smallest triangle in this iteration, multiply this by 12 then add it to the area of the pervious triangle. This goes on for the next iteration.

From the table at the very gaining of the part, we can see that the perimeter for the iterations of Kochs’ triangles make a up a geometric sequence whose formula is Un = 729/4 x 4^(iteration no)/3. The increments between these numbers are always some multiple of 3. This shows that the perimeter of Koch’s snowflake is a geometric sequence.

The area of the iterations, on the other hand, are increasing but its increments are decreasing from 947 to 421 to 187. The area is not a series.

As Koch’s fractal snowflake can infinitely add more triangles to itself as it will always have a straight line that can have a triangle added to it every iteration, the perimeter of Koch’s triangle is considered boundless and, therefore, infinite.

If you’d like to further explore and/or understand Koch’s snowflakes, specifically its mathematical origin, feel free to click this link:

http://gofiguremath.org/fractals/koch-snowflake/

Part C: Investigation C: Yet Another Triangle, Thanks Sierpinski

(2019). Education Bookshelf Mathematics Analysis and Approaches Higher Level.

[online] Bookshelf.oxfordsecondary.co.uk. Available at:

https://bookshelf.oxfordsecondary.co.uk/contents/428/index.html [Accessed

30 Oct. 2019].

These mathematicians really can’t just sit down and not make any new triangles can they?

| Stage | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Number of green triangles | 1 | 3 | 9 | 27 |

| Length of one side of one green triangle | 1 | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/8 |

| Area of each green triangle | 1 | 1/4 | 1/16 | 1/64 |

| Stage | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Number of green triangles | 81 | 243 | 729 |

| Length of one green triangle | 1/16 | 1/32 | 1/64 |

| Area of each green triangle | 1/256 | 1/1024 | 1/4096 |

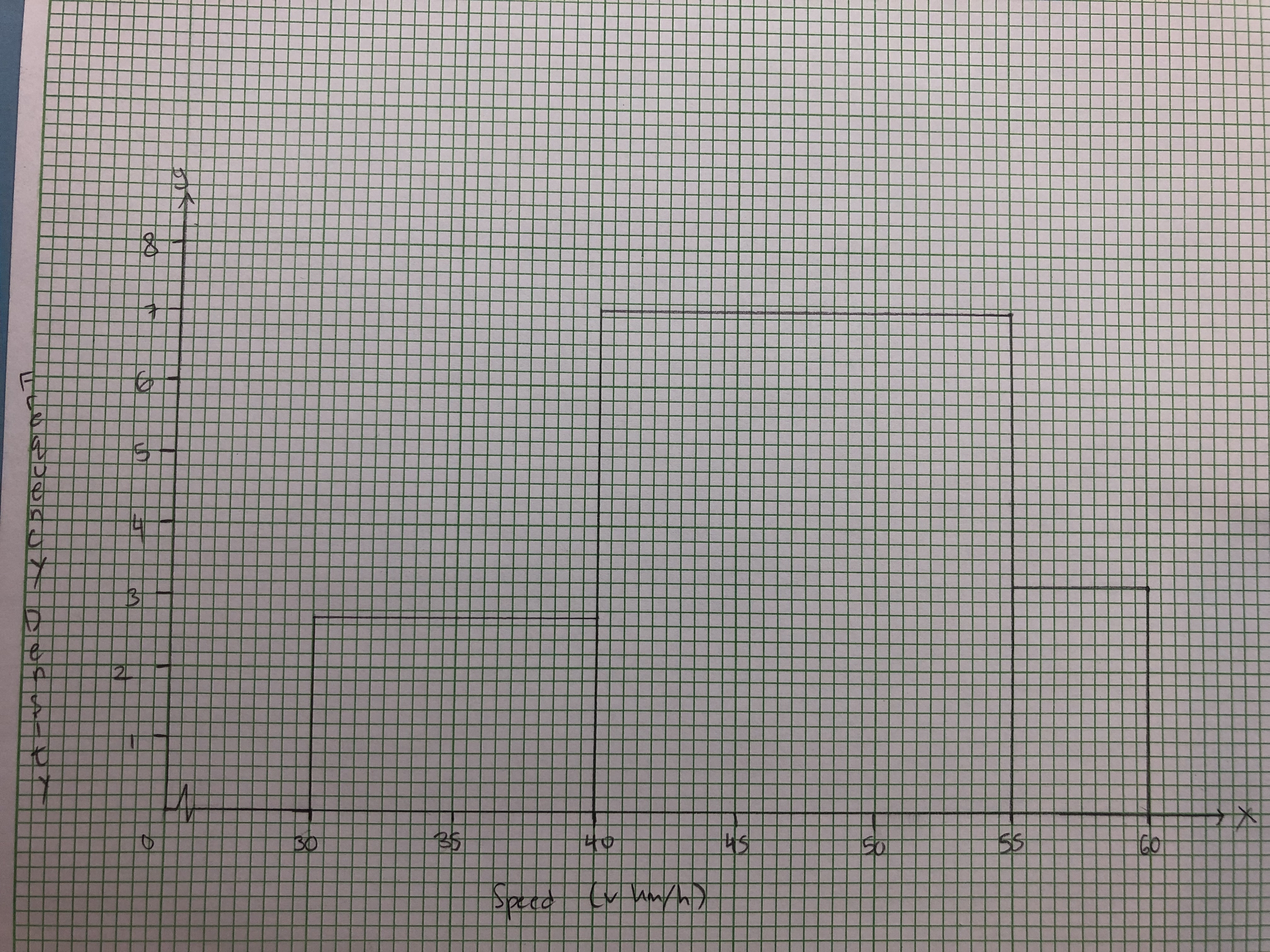

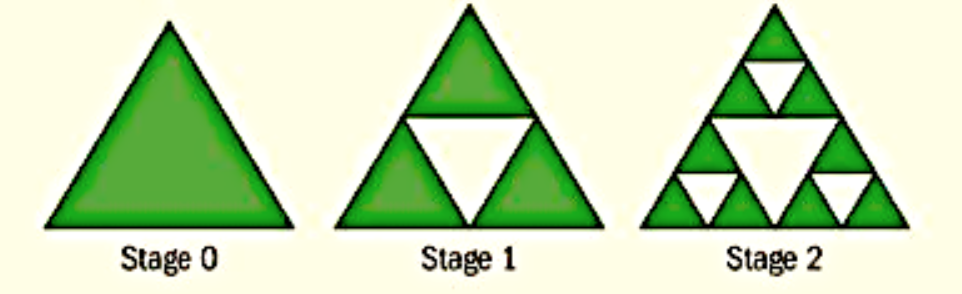

Well, anyway, for this task, we need to, first, find the next stage of Sierpinski’s triangle by observing the pattern between the first three stages then applying this pattern to get the next stage. Next, we had to fill out a table on the information about the number of green triangles, the length of one side of one green triangle and the area of each green triangle for stages 0 to 3, find the patterns of the first three rows of this table, what they have in common, find a formula to find the above info for triangles of stages 4, 5, 6, etc. and compare the numbers we obtained.

The topics involved are, again, geometry, specifically of triangles, perimeter and area of a triangle, infinity, geometric sequences and/or trends between sets of numbers.

We can see that the number of green triangles is a geometric series with the formula of 3^(stage no).

As for the length of one side of one green triangle, the formula is 1/2^(stage no), in other words it’s also a geometric sequence.

The area of each green triangle’s formula is 1/4^(stage no). Surprise, surprise, it’s also a geometric sequence.

All these three patters are geometric sequences; you find the next term by multiplying the pervious term with a fixed constant.

Therefore, if we we wanted to find the patterns for the 4th, 5th and 6th stages, it would be like the above table.

I could compare the sets of numbers ordained by lining up the sequences above one another and seeing the constants for each geometric sequence. We can then see the similarities in the numbers we’d get using the formulas we have and the similar ratio between same stage, different sequence numbers, which would all make up its own geometric sequence.

Sierpinski’s triangle is, again, infinite, as there will always be a space for a new triangle inside of the already existing triangles. As the size of the triangles decreases, the area of each triangle decreases, while, funnily enough, the total perimeter of the triangles increase suntil it approaches infinite. This happens because the area of the triangles decreases as the space for the triangles decreases while the quantity of the triangles increases. This results in an infinitely decreasing area and an infinitely increasing perimeter.

And so concludes the end of my triangle musings that lasted from morn to night as I followed in Koch’s and Sierpinski’s (triangle) steps.

If you’d like to explore more of the build of Sierpinski’s triangle, feel free to explore this link:

Reflection

From these investigations, I find I acquired better knowledge of geometric patterns and how shapes, triangles in particular, have a pattern with their perimeter and area. Triangles can also expand infinitely as snowflakes as exemplified by Koch’s snowflakes. As for skills I acquired, I found that I can assume sequences more quickly and find a pattern with triangles as well as think spatially better with these geometric investigations.

I can use these skills in my life to find a pattern in the happenings in my life and learn to manipulate the information I have to understand the context of something that is not necessarily mathematical better. This could be helpful in social situations where I have to watch out for social cues and can put a stop to any damaging patterns, such as snacking, I find in my life.

IB Learner Profile

IB learners are open-minded, knowledgable thinkers. IB learners are individuals who develop and use a good foundational understanding to explore many different subjects using critical and creative thinking to analyse the problem before them from many different points of view that would give them the chance to further their understanding.

With these exercises, I became more open-minded with the ways I can use and manipulate the information I have geometrically. I was also able to think more critically as I struggled to initially find the pattern between the sequences and numbers and, especially, find the perimeter and area of the triangles in investigation B. Lastly, I became more knowledgable of the geometry behind seemingly complex shapes such as snowflakes that really are just infinite triangles as well as the pattern existing in nature of these snowflakes and how sequences work.

Unforgettable Moments: me and math mutually tearing each other apart ver.

#igcsemath2020

#firstbatch TT

Sadly, I’m not one to take a lot of photos nor do I have too many memories to reminisce, however, I can show you this meme as a representation of how I felt as I finished writing my first math journal meme.

I had to write an journal and just being blown away with all the things we could do with our blog, though, granted, I’m still unable to achieve my ideal blog even with all these features due to many factors including my shortcomings and lack of understanding of wordpress. I won’t, however, rue the first time I published my e-journal and the euphoria of having my own place in the world wide web.

Bibliography

Interactivate: Sierpinski’s Triangle. (2019). Retrieved 20 November 2019, from http://www.shodor.org/interactivate/activities/SierpinskiTriangle/

Lamb, E. (2019). A Few of My Favorite Spaces: The Sierpinski Triangle. [online] Scientific American Blog Network. Available at: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/roots-of-unity/a-few-of-my-favorite-spaces-the-sierpinski-triangle/ [Accessed 20 Nov. 2019].

athall, J., Harcet, J., Harrison, R., Heinrichs, L. and Torres-Skoumal, M. (2019). Education Bookshelf Mathematics Analysis and Approaches Higher Level. [online] Bookshelf.oxfordsecondary.co.uk. Available at: https://bookshelf.oxfordsecondary.co.uk/contents/428/index.html [Accessed 30 Oct. 2019].

Go Figure. (2019). Koch Snowflake. [online] Available at: http://gofiguremath.org/fractals/koch-snowflake/ [Accessed 20 Nov. 2019].

(2019). [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.deviantart.com/mezzaninex/art/Sierpinski-Triangle-Variation-53820973

(2019). [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.deviantart.com/mezzaninex/art/Sierpinski-Triangle-Variation-53820973